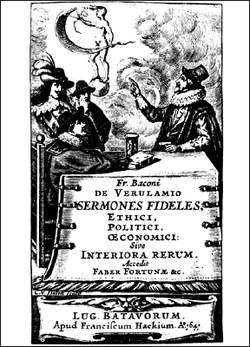

Bacon, Francis

(religion, spiritualism, and occult)Francis Bacon (1561–1626) was an English philosopher often regarded as the father (or one of the fathers) of modern science. He was famous for his advocacy of the empirical method. Perhaps because he perceived it as resting on an empirical base, he was an ardent champion of astrology.

Bacon, Francis

Born Jan. 22, 1561, in London; died there on Apr. 9, 1626. English philosopher; originator of English materialism.

In 1584, Bacon was elected to Parliament. In 1617 he became lord keeper of the press and later lord chancellor; he was created Baron Verulam and made Viscount St. Albans. In 1621 he was brought to trial on the charge of bribery, convicted, and relieved of all his duties. Though pardoned by the king, he did not return to government service and devoted the last years of his life to scientific and literary work.

Bacon’s philosophy took shape in the atmosphere of general scientific and cultural progress of the countries of Europe that had entered upon the path of capitalist development and of the liberation of science from the Scholastic fetters of clerical dogmatism. All his life, Bacon worked upon a large-scale plan for the Instauratio magna.

Science, according to Bacon, must give man power over nature, increase his might, and improve his life. From this point of view, he criticized Scholasticism and its syllogistic deductive method, which he contrasted to the appeal to experience and the refinement of its inductions by emphasizing the importance of experiments. In the words of Marx, for Bacon “science is an empirical science and consists of the application of rational method to sensory data” (K. Marx and F. Engels, Soch., 2nd ed., vol. 2, p. 142). In elaborating rules for the application of the inductive method which he proposed, Bacon compiled tables of the presence, absence, and degree of various properties in individual objects of a given class. The mass of facts compiled in this manner was to make up the third part of his Natural and Experimental History.

Bacon’s emphasis on the importance of method allowed him to propose a principle, which is very important in teaching, according to which the goal of education is not the accumulation of the greatest amount of knowledge possible but rather the ability to use methods in order to gain knowledge. Bacon divided all extant and possible knowledge in accordance with the three faculties of the human mind: history corresponds to memory; poetry corresponds to imagination; and philosophy, including the study of god, nature, and man, corresponds to reason.

Bacon believed that the reason for errors in reasoning was false ideas—“specters,” or “idols,” of four kinds: “specters of the tribe,” rooted in the very nature of the human race and caused by man’s attempt to view nature by analogy with himself; “specters of the cave,” which arise from the individual personal characteristics; “specters of the marketplace,” bred by an uncritical attitude to prevailing opinions and to incorrect usage of words; and “specters of the theater,” or false perception of reality based on blind faith in authority and traditional dogmatic systems similar to the deceptive verisimilitude of theatrical performances. Bacon regarded matter as the objective diversity of sensory qualities perceived by man; Bacon’s concept of matter had not yet become mechanistic as it did later with Galileo, Descartes, and Hobbes.

Bacon’s teaching exerted an enormous influence on the subsequent development of science and philosophy and made possible the formation of T. Hobbes’ materialism and the sensualism of J. Locke and his followers. Bacon’s logical method was the point of departure for the development of inductive logic, especially that of J. S. Mill. Bacon’s appeal to the experimental study of nature was a catalyst to natural science in the 17th century and played an important role in the creation of scientific organizations—for example, the Royal Society of London. Bacon’s classification of knowledge was adopted by the French enlighteners—the Encyclopedists.

WORKS

The Works …, vols. 1-14. London, 1857-74. (Reprinted: London, 1968.)In Russian translation:

Sobr. soch., vols. 1-2. St. Petersburg, 1874.

O printsipakh i nachalakh. Moscow, 1937.

Novyi organon. Moscow, 1938.

Novaia Atlantida, 2nd ed. Moscow, 1962.

REFERENCES

Herzen, A. I. Izbr. filosofskie proizvedeniia, vol. 1. [Moscow] 1948. Pages 239-270.Fisher, K. Real’naia filosofiia i ee vek: Frantsisk Bekon Verulamskii, 2nd ed. St. Petersburg, 1870.

Milonov, K. K. Filosofiia Frantsiska Bekona. Moscow, 1924.

Subbotnik, S. Frensis Bekon. Moscow, 1937.

Mel’vil’, M. N. Frensis Bekon. Moscow, 1961.

Frost, W. Bacon und die Naturphilosophie. Munich, 1927.

Anderson, F. H. The Philosophy of F. Bacon. Chicago, 1948.

Green, A. W. Sir F. Bacon. New York [1966].

M. N. MEL’VIL’