locomotion

[‚lō·kə′mō·shən]Locomotion

in animals and man, a variety of movement, described by an active shift of the body in space, that includes swimming, flying, and various kinds of movement on the ground (including man’s walking and running).

Locomotion plays an enormously important role in the life of animals. For example, they move when seeking food and escaping enemies. There are many kinds of locomotion, from the very simplest amoeboid movements of some unicellular organisms to complex locomotor acts.

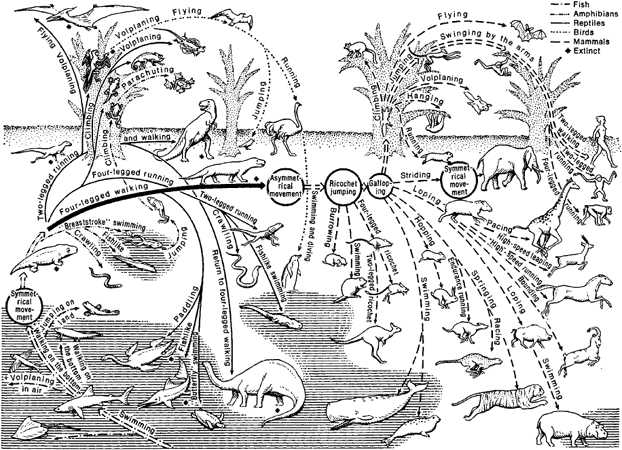

The kinds of locomotion have changed and become more complex during the course of animal evolution, and they have largely determined the structural characteristics of the animals. The appearance of new kinds of locomotion is associated with improvements of the locomotor apparatus, the sense organs, and, especially, the central nervous system. Locomotion is most complex and varied in vertebrates, a brilliant example of the relationship between form and function in evolution (see Figure 1); it includes swimming, flying, gliding, climbing, jumping, brachiation (swinging by the arms), and walking and running on four or on two legs.

The various gaits (walk, trot, amble, four-legged or two-legged ricochet, gallop), unlike the methods of locomotion, are determined not by the structure of the locomotor apparatus but by differences in the coordination of the extremities. The changes in locomotion during the course of the transformation of ape to man have played an exceptionally important role: climbing trees facilitated the formation of the grasping organs—the hands— and the transition to walking upright freed the hands for use as organs of work.

REFERENCES

Bernshtein, N. A. Ocherki po fiziologii dvizhenii i fiziologii aktivnosti. Moscow, 1966.Sukhanov, V. B. Obshchaia sistema simmetrichnoi lokomotsii nazemnykh pozvonochnykh i osobennosti peredvizheniia nizshikh tetrapod. Moscow, 1966.

Gambarian, P. P. Beg mlekopitaiushchikh: Prisposobitel’nye osobennosti organov dvizheniia. Leningrad, 1972.

Granit, R. Osnovy reguliatsii dvizhenii. Moscow, 1973. (Translated from English.)

Howell, A. B. Speed in Animals. Chicago, 1944.

Gray, J. Animal Locomotion. London, 1968.