Maya

1Maya

2Maya

(religion, spiritualism, and occult)Five hundred years before Abraham walked the deserts of the Middle East, or about 2500 BCE, the Mayan people were developing their own religious traditions in the rain forests of Guatemala. Their culture flourished all the way up to the Spanish invasion of the sixteenth century.

The Mayan lived in a world chock full of gods. Much of their average day was spent praying for health, rain, crops, luck, and fortune. But the central religious metaphor of Mayan religion was the ceiba tree, the tree of life. It existed in the three realms of earth, air, and atmosphere with its roots in the ground, trunk in the world, and branches in the heavens. Demonstrating its importance in the delicate climate of the rain forest, it literally exhaled the breath of Hunab K'U, the creative force. Gods and goddesses were associated with crops, especially corn, as well as rain, the sun, the moon, and stars, but the Maya knew that when the last tree was gone, people would perish from the earth.

There was a dark side to the religion. Powerful gods demanded powerful sacrifices to propitiate them (see Sacrifice). With great pomp and ceremony and before huge crowds, rituals were enacted during which humans were offered, with much shedding of blood, as tribute to gods who seemed to demand more and more each year. Pictures carved on stone altars often tell a gruesome story. Probably, though this is less certain, drugs were used to induce heightened states of spiritual awareness.

Such sacrificial ritual is a pattern common to many religious traditions. Perhaps because life was so mysterious they somehow felt the need to "pay the supreme sacrifice," or, more often, make someone else do it. It was central to Mayan religious life. But to judge the entire culture and religion on the grisly archaeology of one aspect of it is to miss the many positive attributes that informed an entire American civilization.

Maya

3D animation and visual effects software for Windows and IRIX workstations from Autodesk, Inc. Formerly owned by Alias Systems Corporation, Toronto, Maya is known for its special character animation capabilities that enable human characters to be simulated with flesh tones, wrinkles and folds in clothing. Maya uses the MEL (Maya Embedded Language) scripting language to define sequences. Most films nominated for best visual effects by the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences use Maya and other Alias imaging software. Autodesk acquired Alias in 2006. See Maya screen saver.Maya

an Indian people on the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico (population, 340,000 in 1970) and in Belize (13,000). Their language belongs to the Maya-Quiche family. Some Maya speak Spanish. They are nominally Catholics, but vestiges of pre-Christian beliefs remain among them. Farming is their chief occupation.

The Maya were the creators of one of America’s oldest civilizations, which existed on the territory of present-day southeastern Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala. The rise of the Maya civilization was closely associated with the Olmec culture in Mexico. The ancient Maya engaged in slash-and-burn farming, cultivating maize (corn), beans, squash, tomatoes, root crops, and cotton; they raised turkeys and dogs, the meat of which was used for food, and they also engaged in hunting, fishing, and beekeeping. Cities with stone structures appeared in the first millennium A.D. There are more than 100 known cities, the largest of which are Tikal, Copán, Chichén Itzá, and Uxmal. In the ninth century, most of the Mayan cities fell into ruin, apparently as a result of the invasion of Indian tribes led by the Toltec. In the tenth century, a new Maya-Toltec state arose in Yucatan; it subsequently broke up into independent city-states.

The ruling class in Mayan society was made up of the military aristocracy and the priests (the priesthood had a complex hierarchy). The Maya retained vestiges of clan relations, and slavery was well developed. The inhabitants of the settlements that made up the community bore various obligations. Handicrafts were well-developed in the cities. There was a large merchant class. The Mayas created their own hieroglyphic writing system. They possessed scientific learning in mathematics, medicine, and astronomy (in particular, there existed an elaborate calendar, which was used for determining agricultural work periods). In their religion, the Maya especially revered the gods of rain and wind.

Because of the heroic resistance of the Maya, the Spanish conquest of Yucatán, which had begun in 1527, was prolonged for many decades. The Maya rebelled repeatedly, even after the establishment of Mexican independence (the largest uprisings took place in 1847-54 and 1904).

The ancient Mayan structures, set on stylobates, are stepped tetrahedral pyramids with truncated apexes on which small temples were constructed (for example, the Temple of the Sun in Palenque, second half of the seventh century), and also long, narrow buildings (residences of the rulers, the priesthood, and the aristocracy) grouped around closed courts, and courts for sacred games. Sculpture (first in wood, and later in limestone), represented by reliefs on temple walls and on stelae (highly stylized until the fourth century; more natural in the seventh and early eighth centuries), was particularly well developed in the second half of the eighth century and in the ninth century, when local schools were formed (Piedras Negras, Palenque, Copan, and Quirigua). During this period balanced, multifigured compositions appeared in which bas-relief was freely combined with high relief. Small plastic arts (terra-cotta figurines and articles made of semiprecious stones) reached perfection. Mayan painting is represented by wall murals (the brightly colored temple paintings in Bonampak, second half of the eighth century) and images on pottery vessels (mythological or historical subjects). The pictures in the Mayan hieroglyphic manuscripts are well known (the artistic level of the pictures in the Dresden Codex is outstanding). In the Maya-Toltec period, the major centers of art and architecture on the Yucatán Peninsula were the cities of Chichén Itzá, Uxmal, and Mayapán.

REFERENCES

Landa, D. Soobshchenie o delakh v lukatane, 1556 g. Moscow-Leningrad, 1955. (Translated from Old Spanish.)Narody Ameriki, vol. 2. Moscow, 1959.

Knorozov, Iu. V. Pis’mennost’ indeitsev maiia. Moscow-Leningrad, 1963.

Gallenkamp, C. Maiia. Moscow, 1966. (Translated from English.)

Kuz’mishchev, V. Taina zhretsov maiia. Moscow, 1968.

Kinzhalov, R. V. Iskusstvo drevnikh maiia. Moscow-Leningrad, 1968.

Kinzhalov, R. V. Kul’tura drevnikh maiia. Leningrad, 1971. (Bibliography.)

Morley, S. G. The Ancient Maya, 3rd ed. Stanford [1956].

Coe, M. D. The Maya. New York-Washington, D. C. [1966].

Kidder, A., and C. Samayoa Chinchilla. The Art of the Ancient Maya. New York, 1959.

Martínez Parédes, D. Un continente y una cultura. Mexico City, 1960.

Wadepuhl, W. Die alien Maya und ihre Kultur. Leipzig, 1964.

Maya. [Fribourg] 1964.

Maya

the writing system of the Maya Indians, who inhabited the territory of present-day Mexico (the Yucatan Peninsula), Guatemala, and Honduras; known from monuments of the early centuries of the Common Era and existed until its prohibition by the Spanish church in the 16th century. Three large manuscripts (“codices”) and numerous inscriptions on stone and ceramics have been preserved.

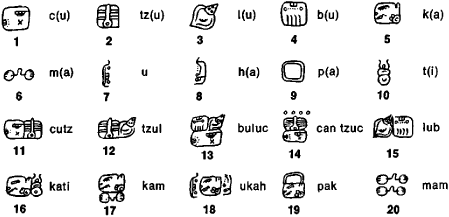

The nature of Maya has provoked controversy among specialists. According to the American scholar J. E. Thompson, it is purely ideographic in nature, and phonetic reading of the writing is supposedly impossible. However, the Soviet linguist Iu. V. Knorozov, who continued the research begun by the French scholar L. de Rosny and the American scholars C. Thomas and B. Whorf, succeeded in discovering among the Maya symbols many phonetic signs, indicating syllables and parts of syllables (see Figure 1).

Knorozov demonstrated that Maya consisted of ideographic symbols (for whole words and morphemes) and phonetic signs, and also radicals (determinatives). His decipherment is based on positional analysis of the words (positional determination of their grammatical class and syntactic function) and cross-verification of hypotheses on the sound of the phonetic signs in words having similar sound elements but different meanings (the meaning of phrases was often suggested by the pictures accompanying the text in the manuscripts). However, a uniform reading and understanding of the manuscripts and inscriptions has not been accomplished: this requires the analysis and reconstruction of the Maya literary language of the turn of the Common Era (the language in which the Maya texts were apparently written, which must have differed from the 16th century Maya language known to scholarship).

REFERENCES

Knorozov, Iu. v. Sistema pis’ma drevnikh maiia. Moscow-Leningrad, 1955.Knorozov, Iu. V. Pis’mennost’ indeitsev maiia. Moscow-Leningrad, 1963.

Rosny, L. de. Essai sur le dechiffrement de l’écrilure hiératique de l’Amerique centrale, 2nd ed. Paris, 1884.

Thomas, C. Central American Hieroglyphic Writing. Washington, D.C., 1904.

Whorf, B. L. Decipherment of the Linguistic Portion of the Maya Hieroglyphs. Washington, D.C., 1942.

Zimmermann, G. Die Hieroglyphen der Maya-Handschriften. Hamburg, 1956.

Thompson, J. E. S. Maya Hieroglyphic Writing, 2nd ed. Norman, Okla., 1960.

Thompson, J. E. S. A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. Norman, Okla., 1962.

A. B. DOLGOPOL’SKII

Maya

one of the most important and universal concepts of ancient and medieval Indian religion, philosophy, and culture. Originally, maya evidently signified the ability of a shaman, magician, or priest to transform things and events of the visible world into one another. Subsequently, the original mythical notion developed into three conceptions of maya, reflecting three aspects of its original meaning.

First, there is the “energetic” conception of maya—a divine creative force associated with the procreative female element (shakti), which serves as the necessary complement to the image of any Hindu divinity and as the means of his self-expression in the universe. Second, there is the “material” conception of maya —the “fabric” of all reality and the end product of all (not only divine) activity; it is thus similar to the concept of the “created universe” as opposed to the uncreated spiritual ultimate reality. Third, there is the “psychological” conception of maya—a synonym for the play of psychological forces (khrida or Hid), the illusoriness of all that is perceived and thought, a screen concealing from human view the higher essence of reality and the true meaning of daily existence.

In the philosophical interpretation of Advaita-Vedanta (doctrine of the maya-vada), maya appears as a capacity that is intermediate between absolute reality (brahman) and absolute unreality (“the round square”). It is neither created nor destructible. The juxtaposition of brahman as the absolute reality and maya as the phenomenological world permitted Sankara, the founder of Advaita-Vedanta, to create a complete metaphysical system in which ontological, epistemological, and psychological antinomies and paradoxes are resolved by introducing the concept of the levels of reality forming the structure of maya.

In certain religious cults (particularly Sivaism), maya appears in anthropomorphic form as the spouse of Siva.

REFERENCES

Shastri, P. D. The Doctrine of Maya in Vedanta. London, 1911.Deutsch, E. Advaita-Vedanta. Honolulu, 1969.

Saccidanandamurti, K. Revelation and Reason in Advaita-Vedanta. Vizagapatam, 1959.

A. M. PIATIGORSKII