Stirling engine

[′stir·liŋ ‚en·jən]Stirling engine

An engine in which work is performed by the expansion of a gas at high temperature to which heat is supplied through a wall. Like the internal combustion engine, a Stirling engine provides work by means of a cycle in which a piston compresses gas at a low temperature and allows it to expand at a high temperature. In the former case the heat is provided by the internal combustion of fuel in the cylinder, but in the Stirling engine the heat (obtained from externally burning fuel) is supplied to the gas through the wall of the cylinder (see illustration).

The rapid changes desired in the gas temperature are achieved by means of a second piston in the cylinder, called a displacer, which in moving up and down transfers the gas back and forth between two spaces, one at a fixed high temperature and the other at a fixed low temperature. When the displacer is raised, the gas will flow from the hot space via the heater and cooler tubes into the cold space. When it is moved downward, the gas will return to the hot space along the same path. During the first transfer stroke the gas has to yield up a large amount of heat to the cooler; an equal quantity of heat has to be taken up from the heater during the second stroke. See Internal combustion engine

Stirling Engine

an external-combustion engine in which heat, which is converted into mechanical energy, is supplied from without and regenerated. The Stirling engine is named for the British inventor R. Stirling (1790–1878), who in the period between 1816 and 1840 developed an engine with an open cycle operating on heated air. The engine also had a rudimentary regenerator (heat exchanger). However, since it was unwieldy and heavy, it did not find use.

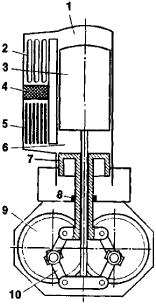

Modern Stirling engines operate on a closed regenerative cycle (Stirling cycle), consisting of two isothermal processes alternating consecutively with two isochoric processes. The working gas in these engines is helium or hydrogen under a pressure of 10–14 meganewtons/m2 (100–140 kilograms-force/cm2). The gas, which is confined to a closed space, is not replaced; during operation it merely changes volume upon heating and cooling. The regenerator acts to divide this space into an upper (hot) and a lower (cold) space (Figure 1). Heat is supplied to the upper space from the heater and removed from the lower space by a cooler, in which water circulates. Two pistons, namely, a power piston and displacer, are housed in the engine’s cylinder. The hot and cold spaces are connected to each other by tubes passing through the heater, regenerator, and cooler.

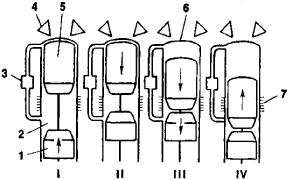

The operating cycle involves four phases (Figure 2). In the first, the displacer is stationary, and the power piston moves upward and compresses the cold working gas in the lower space. The power piston stops once compression is completed, and in the second phase the displacer moves downward, thereby forcing the cold compressed gas from the lower space to the upper; on the way, the gas is heated first in the regenerator and then in the heater. In the third phase, which is the working stroke, the gas expands in the upper space and performs useful work; both pistons move downward together. In the fourth phase, the power piston remains stationary while the displacer moves upward; the working gas moves from the upper space to the lower, initially losing a portion of its heat to the regenerator and then undergoing final cooling in the cooler.

Owing to heat regeneration, the efficiency of Stirling engines can in theory equal the efficiency of internal-combustion engines operating on the Carnot cycle. In practice, however, the efficiency approaches only that of diesels. The conversion of the back-and-forth motion of the pistons into rotational motion is accomplished by a rhombic drive (Figure 1).

A variant of the Stirling engine is the double-acting engine. Here, there are a number of cylinders, which are arranged either in series or in a V-shaped configuration. Each cylinder has just one piston, which provides for compression, expansion, and displacement of the working gas. The operating process is accomplished simultaneously in the spaces on both sides of the piston. The power piston in each cylinder also serves as the displacer for the adjacent cylinder. The complete operating cycle is accomplished over one turn of the crank, as in the two-stroke internal-combustion engine. Double-acting Stirling engines have reduced dimensions and weight.

The fuel in Stirling engines is ignited in atomizers (burners), from which the flames are directed to the heater tubes. Since combustion proceeds with a large excess of air, the combustion products have a lower content of toxic substances than the products of internal-combustion piston engines. Stirling engines can operate on any fuel, including nuclear fuel.

The operation of a Stirling engine is quiet, smooth running (owing to the absence of explosive combustion), highly reliable, and economical (with fuel consumption approaching that of diesel engines). The major disadvantages of Stirling engines are the large size and weight, the high cost relative to internal-combustion piston engines, the difficulty in increasing the speed, the complexity of regulation and control, and the design problems involving the seal, which must withstand the high pressures of the working gas.

Development work on the Stirling engine looks to a reduction in weight and size, the use of less expensive heat-resistant materials and of rational production methods, and improvements in power and economy. Stirling engines for trucks and ships have experienced the most intensive development.

REFERENCES

Smirnov, G. V. Dvigateli vneshnego sgoraniia. Moscow, 1967. Belov, P. M., V. R. Buriachko, and E. I. Akatov. Dvigateli armei-skikh mashin, part 1. Moscow, 1971.N. F. KAIDASH