tachometer

tachometer

[tə′käm·əd·ər]tachymeter, tacheometer, tachometer

tachometer

Tachometer

an instrument for measuring the speed of rotation of the shafts of machines and mechanisms. Centrifugal, mechanical, eddy-current, and electric tachometers are most common; pneumatic and velocity-head, or hydraulic, tachometers are used less frequently.

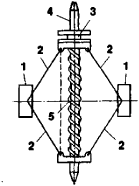

In a mechanical centrifugal tachometer (Figure 1), a sliding

coupling is mounted on a shaft. The coupling has hinged arms carrying weights that spread apart when the shaft rotates, moving the sliding coupling along the shaft against a counterbalancing spring. The position of the coupling on the shaft depends on the speed of rotation and is transmitted by an arm mechanism to an indicator pointer; the indicator dial is calibrated in revolutions per minute. The tachometer shaft may be driven directly, by the controlled mechanism, or indirectly, by a flexible shaft.

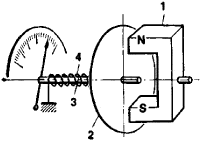

An eddy-current tachometer (Figure 2) uses the interaction of the magnetic fields generated by a permanent magnet and a rotor, whose speed of rotation is proportional to the eddy currents generated. The currents tend to deflect a disk, which is mounted on the shaft and restrained by a spring, through a certain angle. The deflection of the disk, which is rigidly connected to a pointer, is indicated on a dial.

Electric tachometers may be of the generator or impulse type. In tachometer generators the electromotive force of a DC or AC generator is proportional to the angular velocity, from which the shaft speed can be determined; the readings are transmitted to a remote measuring instrument. The operation of impulse tachometers is based on conversion of pulses generated in the primary circuit of an ignition system by the opening of interrupter contacts into a current that is fed to a permanent-magnet indicator. The frequency of pulses in the primary circuit is proportional to the speed of rotation of the engine shaft.

A. A. SABININ