blood pressure

blood pressure

[′bləd ‚presh·ər]Blood Pressure

the hydrodynamic pressure of blood in the blood vessels; it arises as a result of the work of the heart, which pumps the blood into the vascular system, and the resistance of the vessels.

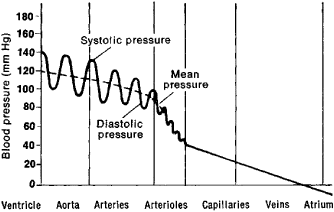

The level of the blood pressure in the arteries, veins, and capillaries varies and is a measure of the body’s functional condition. Arterial pressure undergoes rhythmic variations, increasing during contraction of the heart (systole) and decreasing during the period of its relaxation (diastole). Each new portion of blood discharged by the heart distends the elastic walls of the aorta and central arteries. During the cardiac pause the distended walls of the arteries collapse and push the blood through the arterioles, capillaries, and veins. In man and in many other mammals, the maximum (systolic) pressure is about 120 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg), and the minimum (diastolic) pressure is about 70 mm Hg. The difference between these two values (the amplitude- of pressure change with each heart contraction) is called the pulse pressure. Under physical or emotional stress a short-term increase in arterial pressure occurs, which represents a physiological adaptive reaction. Arterial pressure may be measured by the direct method—that is, insertion into the vessel of a cannula that is connected by a tube with a manometer (the Englishman S. Hales first measured arterial pressure in this way in 1733)—or by an indirect method—that is, by a sphygmomanometer. In man, the arterial blood pressure is usually measured on the arm above the elbow; the value thus determined corresponds to the blood pressure only in that artery and not the entire body. However, the figures obtained make it possible to form an opinion about the blood pressure of the person being examined.

When the blood passes through the capillaries, the blood pressure drops from approximately 40 mm Hg at the arteriole endings to 10 mm Hg at the place where the capillaries shade into the venules. This decrease in blood pressure is caused by the friction of the blood against the walls of the small vessels; it maintains the flow of blood in them. The level of capillary pressure depends on the tonus of the arterioles and on venous pressure and to a considerable degree determines the conditions of the exchange of substances between the blood and the tissues. In the veins a further drop in blood pressure occurs; at the ostia venae cavae blood pressure drops below atmospheric pressure, which is due to the suction of the negative pressure in the thorax (see Figure 1). Venous pressure is measured by the direct method —insertion into the vein of a needle connected to a manometer. The level and variations in blood pressure act on the baroreceptors of the vascular system; thus, neural and humoral reactions occur, which are directed toward maintaining the blood pressure at the level characteristic for the given organism and toward self-regulation of blood circulation.

G. I. KOSITSKII

In man, the average arterial blood pressure is 115–125 mm Hg in systole (maximum) and 70–80 mm Hg in diastole (minimum). The average levels change with age.

| Table 1. Arterial pressure (mm Hg) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | Systolic pressure | Diastolic pressure | ||||||

| 16-20. . . . . . . . . . | 100-120 | 70-80 | ||||||

| 20-40. . . . . . . . . . | 120-130 | 70-80 | ||||||

| 40-60. . . . . . . . . . | up to 140 | up to 90 | ||||||

| over 60. . . . . . . . . . | up to 150 | up to 90 | ||||||

Blood pressure that is persistently higher than the indicated figures, hypertension, may be a symptom of a number of diseases (hypertensive disease, nephritis). Low blood pressure, hypotension, may be physiological, may accompany a number of pathological states, or may be a separate disease.

REFERENCES

Val’dman, V. A. Venoznoe davlenie i venoznyi tonus, 2nd ed. Leningrad, 1947.Kositskii, G. I. Zvukovoi metod issledovaniia arterial’nogo davleniia. Moscow, 1959.

Savitskii, N. N. Biofizicheskie osnovy krovoobrashcheniia i klinicheskie metody izucheniia gemodinamiki, 2nd ed. Leningrad, 1963.