Urinary system

The urinary system consists of the kidneys, urinary ducts, and bladder. Similarities are not particularly evident among the many and varied types of excretory organs found among vertebrates. The variations that are encountered are undoubtedly related to problems with which vertebrates have had to cope in adapting to different environmental conditions.

Kidneys

In reptiles, birds, and mammals three types of kidneys are usually recognized: the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros. These appear in succession during embryonic development, but only the metanephros persists in the adult.

The metanephric kidneys of reptiles lie in the posterior part of the abdominal cavity, usually in the pelvic region. They are small, compact, and often markedly lobulated. The posterior portion on each side is somewhat narrower. In some lizards the hind parts may even fuse. The degree of symmetry varies.

The kidneys of birds are situated in the pelvic region of the body cavity; their posterior ends are usually joined. They are lobulated structures with short ureters which open independently into the cloaca.

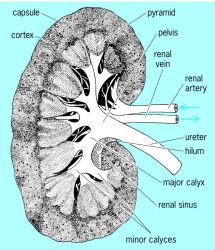

A rather typical mammalian metanephric kidney (Fig. 1) is a compact, bean-shaped organ attached to the dorsal body wall outside the peritoneum. The ureter leaves the medial side at a depression, the hilum. At this point a renal vein also leaves the kidney and a renal artery and nerves enter it. The kidneys of mammals are markedly lobulated in the embryo, and in many forms this condition is retained throughout life. See Kidney

Urinary bladder

At or near the posterior ends of the nephric ducts there frequently is a reservoir for urine. This is the urinary bladder. Actually there are two basic varieties of bladders in vertebrates. One is found in fishes in which the reservoir is no more than an enlargement of the posterior end of each urinary duct. Frequently the urinary ducts are conjoined and a small bladder is formed by expansion of the common duct. The far more common type of bladder is that exhibited by tetrapods. This is a sac which originates embryonically as an outgrowth from the ventral side of the cloaca. Present in all embryonic life, it is exhibited differentially in adults. All amphibians retain the bladder, but it is lacking in snakes, crocodilians, and most lizards; birds, also, with the exception of the ostrich, lack a bladder. It is present in all mammals.

Physiology

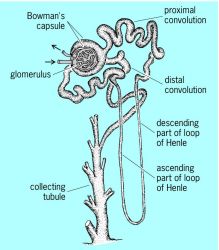

Urine is produced by individual renal nephron units which are fundamentally similar from fish to mammals (Fig. 2); however, the basic structural and functional pattern of these nephrons varies among representatives of the vertebrate classes in accordance with changing environmental demands. Kidneys serve the general function of maintaining the chemical and physical constancy of blood and other body fluids. The most striking modifications are associated particularly with the relative amounts of water made available to the animal. Alterations in degrees of glomerular development, in the structural complexity of renal tubules, and in the architectural disposition of the various nephrons in relation to one another within the kidneys may all represent adaptations made either to conserve or eliminate water.

Regulation of volume

Except for the primitive marine cyclostome Myxine, all modern vertebrates, whether marine, fresh-water, or terrestrial, have concentrations of salt in their blood only one-third or one-half that of seawater. The early development of the glomerulus can be viewed as a device responding to the need for regulating the volume of body fluids. Hence, in a hypotonic fresh-water environment the osmotic influx of water through gills and other permeable body surfaces would be kept in balance by a simple autoregulatory system whereby a rising volume of blood results in increased hydrostatic pressure which in turn elevates the rate of glomerular filtration. Similar devices are found in fresh-water invertebrates where water may be pumped out either as the result of work done by the heart, contractile vacuoles, or cilia found in such specialized “kidneys” as flame bulbs, solenocytes, or nephridia that extract excess water from the body cavity rather than from the circulatory system. Hence, these structures which maintain a constant water content for the invertebrate animal by balancing osmotic influx with hydrostatic output have the same basic parameters as those in vertebrates that regulate the formation of lymph across the endothelial walls of capillaries. See Osmoregulatory mechanisms

Electrolyte balance

A system that regulates volume by producing an ultrafiltrate of blood plasma must conserve inorganic ions and other essential plasma constituents. The salt-conserving operation appears to be a primary function of the renal tubules which encapsulate the glomerulus. As the filtrate passes along their length toward the exterior, inorganic electrolytes are extracted from them through highly specific active cellular resorptive processes which restore plasma constituents to the circulatory system.

Movement of water

Concentration gradients of water are attained across cells of renal tubules by water following the active movement of salt or other solute. Where water is free to follow the active resorption of sodium and covering anions, as in the proximal tubule, an isosmotic condition prevails. Where water is not free to follow salt, as in the distal segment in the absence of antidiuretic hormone, a hypotonic tubular fluid results.

Nitrogenous end products

Of the major categories of organic foodstuffs, end products of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism are easily eliminated mainly in the form of carbon dioxide and water. Proteins, however, are more difficult to eliminate because the primary derivative of their metabolism, ammonia, is a relatively toxic compound. For animals living in an aquatic environment ammonia can be eliminated rapidly by simple diffusion through the gills. However, when ammonia is not free to diffuse into an effectively limitless aquatic environment, its toxicity presents a problem, particularly to embryos of terrestrial forms that develop wholly within tightly encapsulated eggshells or cases. For these forms the detoxication of ammonia is an indispensable requirement for survival. During evolution of the vertebrates two energy-dependent biosynthetic pathways arose which incorporated potentially toxic ammonia into urea and uric acid molecules, respectively. Both of these compounds are relatively harmless, even in high concentrations, but the former needs a relatively large amount of water to ensure its elimination, and uric acid requires a specific energy-demanding tubular secretory process to ensure its efficient excretion. See Urea, Uric acid

Urine concentration

The unique functional feature of the mammalian kidney is its ability to concentrate urine. Human urine can have four times the osmotic concentration of plasma, and some desert rats that survive on a diet of seeds without drinking any water have urine/plasma concentration ratios as high as 17. More aquatic forms such as the beaver have correspondingly poor concentrating ability.

The concentration operation depends on the existence of a decreasing gradient of solute concentration that extends from the tips of the papillae in the inner medulla of the kidney outward toward the cortex. The high concentration of medullary solute is achieved by a double hairpin countercurrent multiplier system which is powered by the active removal of salt from urine while it traverses the ascending limb of Henle's loop (Fig. 2). The salt is redelivered to the tip of the medulla after it has diffused back into the descending limb of Henle's loop. In this way a hypertonic condition is established in fluid surrounding the terminations of the collecting ducts. Urine is concentrated by an entirely passive process as water leaves the lumen of collecting ducts to come into equilibrium with the hypertonic fluid surrounding its terminations. See Urine