judgment

, judgementJudgment

(prigovor), a decision delivered by a court after hearing a criminal case. The judgment establishes the guilt or innocence of the defendant and the sentence for a guilty person. It also establishes any other legal consequences of acknowledging the guilt or innocence of the defendant.

In the USSR the state uses the judgment to protect society and citizens against criminal encroachments, since it is in the judgment that the court, on behalf of the state, gives a sociopolitical assessment of the crime and the person who committed it. The law imposes high requirements on the judgment. It must be legal, substantiated, just, convincing, and well-reasoned. To meet these requirements, the judgment must be based on the evidence heard by the court in session, and it must express the objective truth.

There are two types of judgments in Soviet criminal procedure: conviction and acquittal. If the act has lost its social danger by the time of the trial or the person who committed it is no longer socially dangerous, the court delivers a guilty verdict without imposing a punishment. An acquittal is rendered where the elements of the crime have not been established or the participation of the defendant in the commission of the crime has not been proved.

Each judgment has three parts: an introductory part, a descriptive part (description and reasoning or only reasoning), and a resolutory part.

In view of the exceptional importance of the judgment, criminal procedural law provides a special procedure for rendering and announcing a judgment. The judgment is reached in the conference room where only members of the court for the given case can be present (the law protects the secrecy of the deliberations of the court). The deliberations are directed by the presiding judge. All questions are decided by a simple majority of votes, and the vote of a people’s assessor is equivalent to the vote of the presiding judge. A judge who is in the minority has the right to present a special opinion. The judgment is signed by all the judges, including the dissenting judge. After the judgment is signed it is announced in court, and all those present in the courtroom stand to hear it.

The judgment is given in the language in which the trial was conducted. If the judgment is given in a language that the defendant does not understand, it must be read after it is announced in a translation in the native language of the defendant or in another language that the defendant knows. A copy of the judgment is given to the convicted or acquitted person. The possibility of lodging an appeal or protest through the organs of court supervision guarantees that only legal and substantiated judgments will be enforced.

Judgment

(1) A proposition.

(2) A mental act expressing the speaker’s relationship to the content of a statement, or utterance, through affirmation of its modality and usually associated with the psychological state of conviction or belief. Reflecting the profoundly semantic nature of speech (and of linguistic thought in general), judgments in this sense, in contrast to propositions, always have a modal and evaluative character.

If a statement is evaluated only with respect to its truth-value—the mode of affirmation being “A is true” or “A is false”—the judgment is called assertoric. If what is affirmed is the possibility (of the truth) of what is stated—as in “A is possible (possibly true)” or “It is possible that A (is true)”—the judgment is called problematic. Finally, when it is the necessity (of the truth) of a statement that is affirmed—as in “A is necessary (necessarily true)” or “It must be that A (is true)”—the judgment is called apodictic. There are, of course, other possible evaluations of a statement, such as “A is beautiful” or “A is unfortunate,” but there is as yet no formulation or formal study of this kind of judgment in any theory of logic.

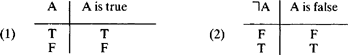

In classical logic, the only means of evaluating a statement is covered by the first mode considered above; from this point of view, however, a statement is indistinguishable from the assertoric affirmation of a statement, as shown in (1) and (2).

Hence in classical logic the terms “judgment” and “proposition” are synonymous, and judgments are not singled out as independent objects of inquiry. It is only in modal logic that judgments actually become a subject for special study.

REFERENCE

Church, A. Vvedenie v matematicheskuiu logiku, vol. 1. Moscow, 1960. Subsection 04. (Translated from English.)M. M. NOVOSELOV